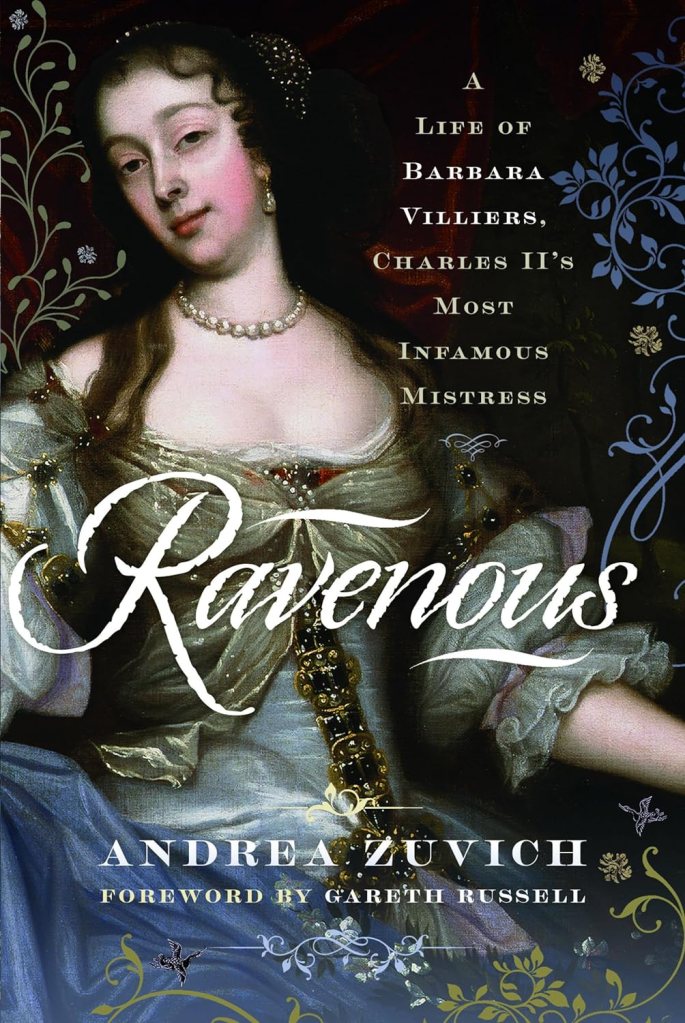

My good friend and historian Andrea Zuvich kindly provided me with a copy of her latest book “Ravenous” which I was happy to read and review. As the title infers, Villers is not a very sympathetic or even likable character. Zuvich’s treatment of Barbara is very even handed, neither extolling her character nor denigrating her in the process. By providing the complex details of Barbara’s life, we get a complete view of her.

Barbara’s family, the Villiers, were integral operators in the Stuart monarchy beginning with the reign of James I. Zuvich gives us some background into the family, and Barbara was related to one of the more minor family members. From the time she was a teenager, she engaged in carnal relations with an aristocratic member of the court. Although this relationship did not result in a marriage, Barbara had a connection with the man throughout her whole life. Early on, Barbara managed to gain access to King Charles II, even while he was in exile and before his restoration to the English throne. By the time this happened, she was Charles’ maîtresse en titre, in the tradition of his grandfather, King Henri IV of France.

This would be Charles II’s longest lasting relationship, especially due to the birth of several children with Barbara, in effect creating a family unit which he supported until his death. Initially, Barbara engaged in political and diplomatic matters at court and as Zuvich explains, played a role in the disgrace of Henry Hyde, Charles’ chancellor, among others. Charles endowed Barbara with various sizable sources of income, something people grumbled about. He also elevated her, first to the title of Countess of Castlemaine and later to the title of Duchess of Cleveland. All of their male children together were given aristocratic titles and the female children made good marriages.

Later in her life, Barbara engaged in behavior, such as taking lovers and gambling large amounts of money which caused embarrassment for Charles, and she slowly disappeared from any meaningful influence and authority at court. Zuvich has found numerous references to debts and lawsuits for collection in Barbara’s name that make for interesting reading. I especially liked Andrea’s take on the relationship between King Charles and his wife, Queen Catherine of Braganza. She is very fair in her treatment of the queen.

Andrea’s research is meticulous, and she obviously went to great lengths to explore the archives to find intriguing nuggets about Barbara’s life. She also investigates and reports on all the many interrelationships between Barbara Villiers and numerous members of the Restoration Court. There is an extensive collection of illustrations in the book, documenting Barbara’s beauty throughout her life. The book is well written and well-researched. For anyone interested in the Barbara and various intrigues and dealings and interactions between courtiers of the Stuart Restoration court, I can highly recommend “Ravenous”.

For US buyers: Ravenous: A Life of Barbara Villers, Charles II’s Most Infamous Mistress

For UK buyers: Ravenous: A Life of Barbara Villiers, Charles II’s Most Infamous Mistress

You must be logged in to post a comment.