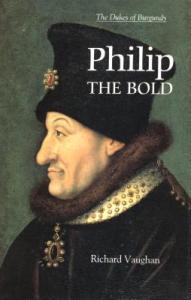

Once again, Vaughan delivers with this biography of Philip the Good, third volume of the four volumes series on the Valois Dukes of Burgundy. The subtitle of this book is “The Apogee of Burgundy”. It was during Philip’s reign that Burgundy was at its highest point as a powerful European state and he ruled the longest of any of the Dukes of Burgundy.

Philip was Duke during the end of the struggles between England and France, known as the Hundred Years War. Burgundy played an integral part, sometimes on the side of England, sometimes on the side of France. While these three entities fought and made peace among themselves, Philip was conquering and annexing various part of Northern Europe. Philip fought with Jacqueline of Hainault for several years and finally broke her resolve. She named Philip as her successor and when she died in 1436, he was ruler of Holland, Zeeland and Hainault. He managed to annex Luxembourg into his territories also.

Philip would have to contend with several rebellions in some of his principal cities. He dealt with artisan rebels in Liège and Ghent along with others. King Charles VII of France was a real thorn in Philip’s side. Even though Charles was guilty of murdering Philip’s father John the Fearless, and despite Charles’ many attempts to frustrate and even annex parts of Philip’s empire, the Duke was deferential. He thought of himself as the premier nobleman in France and took his chivalric duties to heart. In fact, Charles VII and his son Louis XI were dead set on taking Burgundy into the royal domain and this would actually come to fruition in 1477.

This book is packed with great information. Vaughan recounts some of the many marriage alliances Philip made with his immediate family and with his nieces and nephews. There is chapter on the Duke and his court which explains how Philip loved pomp and circumstance and would great pageants and spectacles and massive jousting tournaments. He started the chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece and collected medieval manuscripts. Philip was married three times with his final wife, Isabel of Portugal being his best and most helpful wife. She would act in his name many times and was instrumental in negotiating many alliances and trade agreements.

Other chapters in the book deal with the economics and trade of Burgundy, financial affairs, his relations with the Church, Philip’s attempts to gain a crown for some of his territories and his attempt to mount a religious crusade for the relief of Constantinople. One of the most fascinating sections of the book is a long list drawn up by one of Philip’s administrators listing what would be needed for the crusade in the way of people, supplies, transportation and how much it would all cost. Like the other two volumes in this series, this one is a great read. Looking forward to the next chapter, the son of Philip the Good, Charles the Bold.

You must be logged in to post a comment.